FTC Commissioner Testifies on Harm Caused By Generic Drug Exclusion Agreements

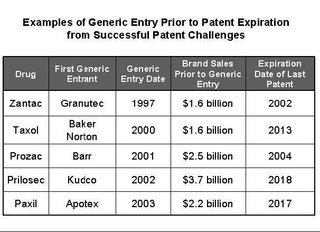

The issue of [generic drug] exclusion payments has been the subject ofAccording to the Commission, experience has borne out the efficacy of the Hatch-Waxman Act process and the correctness of its premises – i.e., that many patents will not stand in the way of generic entry if challenged, and that successful challenges can yield enormous benefits to consumers:

significant debate, but the Commission’s position is clear. Where a patent

holder makes a payment to a challenger to induce it to agree to a later entry

than it would otherwise agree to, consumers are harmed either because a

settlement with an earlier entry date might have been reached, or because

continuation of the litigation without settlement would yield a greater prospect

of competition.

Some who disagree with the Commission’s position argue that we must presume

the validity of the patent, and even infringement, and its exclusionary power

for the full term unless patent litigation proves otherwise. They also argue

that we must permit parties to settle patent litigation, which they may choose

to do regardless of their positions on the merits, according to their own risk

calculus at the time. These arguments, however, ignore both the law and the

facts. There is no question that the result of patent litigation, and therefore

the timing of generic entry, is uncertain. But the antitrust laws prohibit the

paying of a potential competitor, as well as an existing competitor, to stay out

of the market, even if the entry is uncertain. We disagree with the argument

that generic entry before the end of a patent term is too uncertain or unlikely

to be of competitive concern, because Congress spoke on the issue and we know

that would-be generic entrants have enjoyed a nearly 75 percent success rate in

patent litigation initiated under Hatch-Waxman. As for the argument that

challenging such payoffs will deter settlements, which generally are favored,

legitimate patent settlements – using means other than exclusion payments –

continued to occur without hindrance from the Commission decision.

By increasing the likelihood of generic entry, however, the statute also increases the incentive for brand and generic manufacturers to conspire to share, rather than compete for, the expected profits generated by sales of both brand and generic drugs. According to the Commissioner's testimony

By increasing the likelihood of generic entry, however, the statute also increases the incentive for brand and generic manufacturers to conspire to share, rather than compete for, the expected profits generated by sales of both brand and generic drugs. According to the Commissioner's testimonyIn the U.S., a brand-name drug manufacturer seeking to market a new drug product must first obtain FDA approval by filing a New Drug Application ("NDA") that, among other things, demonstrates the drug product’s safety and efficacy. At the time the NDA is filed, the NDA filer also must provide the FDA with certain categories of information regarding patents that cover the drug that is the subject of its NDA. Upon receipt of the patent information, the FDA is required to list it in an agency publication entitled "Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence," commonly known as the "Orange Book.In nearly any case in which generic entry is contemplated, the profit that

the generic anticipates will be much less than the profit the brand-drug company

makes from the same sales. Consequently, it typically will be more profitable

for both parties if the brand-name manufacturer pays the generic manufacturer to

settle the patent dispute and agree to defer entry. Although both the brand-name

company and the generic company are better off with the settlement, consumers

lose the possibility of an earlier generic entry, either because the generic

company would have prevailed in the lawsuit or the parties would have negotiated

a settlement with an earlier entry date but no payment. Instead, consumers are

left with the guarantee of delayed generic entry and paying higher prices.The Commission has challenged patent settlements when it believes that brand-name and generic companies have eliminated the potential competition between them and shared the resulting profits. . . . Initially, the Commission’s enforcement efforts in this area appeared significantly to deter anticompetitive behavior. . . . Recent court decisions, however, have taken a lenient view of exclusion payment settlements, essentially holding that such settlements are legal unless the patent was obtained by fraud or that the infringement suit itself was a sham.

Rather than requiring a generic manufacturer to repeat the costly and time-consuming NDA process, the Hatch-Waxman Act Amendments permit the company to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application ("ANDA"), which incorporates data that the "pioneer" manufacturer has already submitted to the FDA regarding the branded drug’s safety and efficacy. The ANDA filer must demonstrate that the generic drug is "bioequivalent" to the relevant branded product. The ANDA must also contain, among other things, a certification regarding each patent listed in the Orange Book in conjunction with the relevant NDA. One way to satisfy this requirement is to provide a "Paragraph IV" certification, asserting that the patent in question is invalid or not infringed.

An ANDA filer that makes a Paragraph IV certification must provide notice, including a detailed statement of the factual and legal bases for the ANDA filer’s assertion that the patent is invalid or not infringed, to both the patent holder and the NDA filer. Once the ANDA filer has provided such notice, a patent holder wishing to take advantage of the statutory stay provision must bring an infringement suit within 45 days. If the patent holder does not bring suit within 45 days, the FDA may approve the ANDA immediately.

Filing a Paragraph IV certification is a prerequisite to operation of the two most competitively sensitive provisions of the statute 1) the automatic 30-month stay of approval of the ANDA when a patent holder brings an infringement suit, and 2) the 180 day marketing exclusivity for the first filer of an ANDA.

If the patent holder does bring suit with 45 days after the filing of an ANDA, the filing of that suit triggers an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval of the ANDA. And, without FDA approval, a generic manufacturer cannot bring its product to market. The imposition of a stay can, consequently, forestall generic competition for a substantial period of time.

The second competitively sensitive consequence is the 180-day period of marketing exclusivity. To encourage generic drug manufacturers to challenge questionable patents by filing Paragraph IV certifications – a move that can potentially subject the company to costly and burdensome patent infringement litigation – the Hatch-Waxman Amendments provide that the first generic manufacturer (first-filer) to file an ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification is awarded 180 days of marketing exclusivity, during which the FDA may not approve a potential competitor’s ANDA. The 180-day period is calculated from the date of the first commercial marketing of the generic drug product. The potential impact of the 180-day exclusivity period is further magnified by the fact that, under the prevailing interpretation of the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, a second ANDA filer may not enter the market until the first filer’s 180-day period of marketing exclusivity has expired, even if the first filer substantially delays commencement of the exclusivity period.

"Congress should clarify that dismissal of an action brought by a generic applicant seeking a declaratory judgment constitutes a forfeiture event for the 180-day exclusivity period," testified Commissioner Leibowitz.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home

© 2004-2007 William F. Heinze