The Role of (Intellectual) Property Rights in Contracting

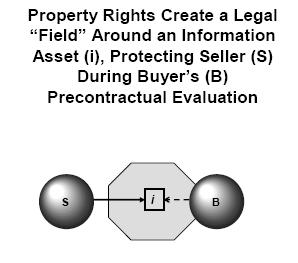

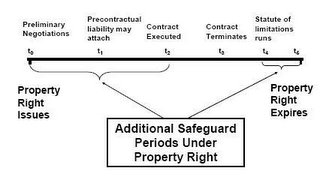

In his essay entitled "A Transactional View of Property Rights," Professor Merges expounds upon two contributions that property rights make to real-world contracting: (1) "precontractual liability," or protection for disclosure of sensitive information in the period leading up to contract formation; and (2) "enforcement flexibility" after a contract is executed, in the form of many subtle but important advantages that accrue to a contracting party who also holds a property right.

According to Professor Merges,

According to Professor Merges,In an economy where contracting is becoming more pervasive, property rights invest contractual exchange with an important dimension. At the initial stage, they facilitate precontractual negotiations. After a contract is signed, they give contracting parties numerous additional enforcement options which, in the aggregate, confer considerable flexibility. In sum, they are valuable adjuncts at every stage of the contracting process.

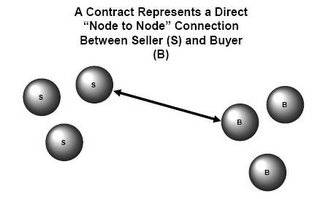

. . . Property rights bring the power of the state to bear on relations between legal “strangers.” By specifying a holder’s rights “against the world,” they create an off-the-rack, mandatory legal relationship between the rightholder and everyone else. Contracts are completely different. A contract signifies a close, voluntary relationship between assenting parties – what one might call a legally “intimate” relationship.

What I have been trying to do in this Essay is to first describe how property works in the hinterland, the transition zone, between legal strangers and legal intimates. Next I have shown how, once parties cross the bridge between the anonymity of property

and the intimacy of contract, property continues as an important presence in the relationship. Property ownership gives a contracting party many small additional options that become collectively valuable if the contract goes bad – if enforcement becomes necessary. And so the power of the state-backed property right continues to exert influence even after legal actors are no longer strangers.Viewed in this light, property and contract are no longer a dichotomous pair. They can be seen to work together toward a common end: the promotion of voluntary, bilateral contracting. Given the rising importance of contracts in the new economy taking shape around us, this harmony at the heart of two of our most basic legal categories seems an important discovery indeed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home

© 2004-2007 William F. Heinze