Structural Equivalents Under §112, ¶ 6 Sent to Jury

The court began by identifying the function of the securing means as "to cause said rod to bear against said channel through the application of substantially equal compressive forces by said securing means in the direction of the vertical axis and applied on either side along said longitudinal axis of said channel." It then went on to address whether the claim recites structure to carry out that function:at least two anchors and an elongated stabilizer comprising a rod having a

diameter and a longitudinal axis . . .securing means which cooperate with each of said anchor seat portions . . . said securing means including second threads which cooperate with the first threads of the seat means to cause said rod to bear against said channel through the application of substantially equal compressive forces by said securing means in the direction of the vertical axis and applied on either side along said longitudinal axis of said channel.

One embodiment of the device was illustrated in Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the patent below:The claim states that the "securing means . . . cooperate with each of said anchor seat portions," id., ll. 44-45, in that the "securing means include[s] second threads which cooperate with the first threads of the seat means to cause [the desired function]," id., ll. 51-57. Although it is the operation of the threads that causes the rod to bear against the channel by applying a compressive force in the direction of the vertical axis, a naked incantation of threads alone does not ensure that substantially equal forces are applied along the longitudinal axis of the rod on opposite sides of the rod-receiving channel. Because there is insufficient structure recited for performing the specified function, § 112, ¶ 6 applies. Thus, we construe the claim "to cover the corresponding structure . . . described in the specification and equivalents thereof."

FIG. 4 (below, left) also shows a cross-section of the anchor seat and nut with the cap and screw and the rod shown in phantom. According to the court, the securing means structure for performing the recited function is described as follows in the specification:

The nut 27 includes internal threads 83 which engage the external threaded area 76 on the anchor seat. The nut 27 is a hex nut which can be tightened relative to the seat 25. As the nut 27 is rotated about the anchor seat 25, it cooperates with the top side of the flange 46,47 to tighten the clamp 25 in relation to the rod support 23. The rod 18 is grasped in the tunnel 84 formed between the rod-receiving channel 54 of the anchor seat 23 and the arch 72 of the cap 25.

The threads 76 on the anchor seat 23 extend downwardly on the seat below the top of the cylindrical surface of the rod 18 as is shown in FIG. 2 and the nut 27 has a relatively constant diameter through the bore as is shown in FIGS. 2 and 4. Accordingly, the nut 27 can be screwed directly onto the anchor seat 23 to compressively hold the rod without the cap 25.

Figures 5 and 7 also depict the rod 18 in the channel created by the anchor seat 23, with the nut 27 securing the rod in place. "Thus," the court concluded, "the structure that corresponds to the claimed function is a nut with internal threads cooperating with the external threads of the anchor seat (an "external nut"). The claim covers that structure and equivalents thereof. "

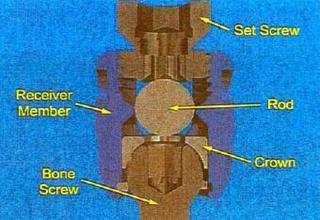

In contrast to this structure, the accused devices [right] employed a "set screw," which features external threads to mate with the receiver member’s internal threads, to hold the rod in the receiver member. The accused devices also included a "crown member" that lies between the rod and the bone screw. The court went on to examine whether the assertedly equivalent structure performs the claimed function in substantially the same way to achieve substantially the same result:

. . .The claimed function has two parts: (1) causing the rod to bear against the channel by applying a compressive force in the direction of the vertical axis; and (2) ensuring that substantially equal forces are applied along the longitudinal axis of the rod on opposite sides—either inside or outside—of the rod-receiving channel. There is no dispute that the set screw applies a compressive force in the direction of the vertical axis. However, there is a genuine issue of material fact as to whether the set screw applies substantially equal forces on opposite sides of the channel, and thus whether there is identity of function.

On the one hand, Cross Medical cites testimony stating that the v-ring on the bottom of the internal set screws creates two points of contact when the set screws are compressed against the rod; that the two points of contact between the set screw and the rod are 180 degrees apart, separated by the drive in the set screw; and that the set screw is intended to be co-axial with the receiver (but because of manufacturing tolerances is not co-axial). (Sherman Dep. of Jan. 29, 2004, at 137-41; Sherman Dep. of Jan. 30, 2004, at 283-84.) On the other hand, Medtronic cites testimony stating that Sherman did not know if the load on the points of contact on either side of the v-ring were equal; that when the implant is functioning in a patient, the screw takes on additional load from the rod; and that anytime the screw is loaded, load will increase on one side of the plug such that forces on the two sides would be unequal. (Id. at 365-66.) Sherman further testified that he did not know if forces would be equal before the screw and anchor seat were implanted, because manufacturing tolerances might impact the forces. (Id. at 366-67.) Drawing inferences in favor of Medtronic, a reasonable juror could find that the forces are not substantially equal on each side of the channel because of manufacturing tolerances and the additional load placed on the screw by the rod when implanted. Crediting Cross Medical’s evidence, a reasonable juror could draw an inference based on Sherman’s testimony that the forces applied to the rod on either side of the channel are substantially equal.

Moreover, there is a genuine issue of material fact as to whether the set screw [right] accomplishes the claimed function in substantially the same way as the external nut. Medtronic has cited the testimony of Dr. Puno stating that he considered using a set screw in 1990 to hold the rod in place but decided against the set screw because of splaying concerns. (Puno Dep. of April 9, 2004, at 32, l. 10-36, l. 24.) Dr. Puno stated that having the side walls of the anchor seat spread apart when the screw was tightened down would be "a bad thing" and "could end up loosening the connection on the rod." (Id. at 35, ll. 7-14.) Although Dr. Puno testified that he thought a set screw and external nut were interchangeable, he qualified his statement when confronted with prior deposition testimony to the opposite effect. (Id. at 37, l. 3–41, l. 23.) Dr. Villarraga stated that the structures were interchangeable because they both could compress a rod into a channel, and because other polyaxial devices utilized set screws. (Villarraga Decl. of April 12, 2004, at 2.) However, Dr. Villarraga neither explained with any specificity why one of ordinary skill in the art at the time the ’555 patent issued would believe the structures to be interchangeable, nor did she refer to any testing. (See id.) Drawing inferences in favor of Medtronic, a reasonable juror could find that the set screw does not compress the rod in substantially the same way based on Dr. Puno’s testimony about the potential for splaying and his conscious decision to avoid the set-screw design. Drawing inferences in favor of Cross Medical, a reasonable juror could find that the set screw compresses the rod in substantially the same way because both employ threads as a compression mechanism, and some statements of Drs. Puno and Villarraga support a finding of interchangeability.

We thus disagree with Medtronic that the equivalents question should be removed from the trier of fact under Chiuminatta. In that case, we held that no reasonable juror could conclude that the differences between "soft round wheels" and a "skid plate" were insubstantial. Chiuminatta, 145 F.3d at 1310. One of the many reasons that we found no equivalents as a matter of law was that the patent at issue discussed the use of wheels for another function, but never disclosed that wheels could perform the same function as the skid plate. Id. In this case, although Medtronic may argue that the fact finder should draw an inference of no interchangeability based on the inventors’ explicit reference to set screws to form a cross-link, see ’555 patent, col. 6, ll. 25-44, and their failure to explicitly recognize set screws as a means for securing the anchor to the bone, we must draw inferences in favor of Cross Medical in evaluating Medtronic’s cross-motion for summary judgment. As discussed supra, we believe that the issue of interchangeability should be left for the trier of fact.

We also reject the other arguments that both sides make in attempting to prevail on equivalents as a matter of law. First, we reject Cross Medical’s argument that the ’004 patent serves as an admission on interchangeability. Even though the ’004 patent, which is assigned to an entity related to Medtronic, suggests that an "internally-threaded nut" is interchangeable with "a set screw or internal plug," ’004 patent, col. 8, ll. 10-32, that patent issued in 2003 and is irrelevant to known interchangeability in 1995, when the ’555 patent issued. See Al-Site, 174 F.3d at 1320 ("[A] structural equivalent under § 112 must have been available at the time of the issuance of the claim."). Second, we reject Medtronic’s contentions that the lack of "bowing" with the set screw and the evidence that the external nut does not function to cause "bowing" in Medtronic’s device are relevant to interchangeability. Even if the external nut causes "bowing" in Medtronic’s device, it is immaterial to the equivalents analysis because "prevention of bowing" is not a limitation of claim 5. See Micro Chem., 194 F.3d at 1258 (cautioning against adopting a function different from that explicitly recited in the claim). Furthermore, although Medtronic argues that the external nut may not work well in Medtronic’s products, any impact this might have on the interchangeability analysis is undercut by a lack of evidentiary support.

In summary, we conclude that there is a genuine issue of material fact with respect to whether a set screw is equivalent to an external nut. Thus, the district court erred in deciding equivalents as a matter of law.

1 Comments:

Hello Mr Heinze,

I enjoyed reading your posting but have a few comments:

The first is in regards to the “genuine issue of material fact as to whether the set screw accomplishes the claimed function in substantially the same way as the external nut.” In my opinion the answer is no. In order to really understand why one would need to know the clinical relevance of both devices. The external nut was initial chosen to apply a downward force and to prevent the tulip (or threaded posts) from splaying. However anyone experienced with this type of device will tell you that this presented at least two problems. The first is that an external driver was required to tighten the original external nut. Adjacent pedicle screws are often close together and occasional the threaded posts are touching. When they are this close, fitting an external wrench around an external nut is challenging. The second problem is that it is more difficult to control a wrench on an external nut. Any off-axis torque or wear of the wrench or nut will potentially allow the wrench to slip off the external nut. Obviously this is dangerous.

The internal set screw solves both of these clinical challenges by first allowing for the presentation of an internal wrench which will not interfere with adjacent screws and secondly by controlling the wrench. An internal wrench if far less likely to slide up and out of an internal hex within an internal set screw. There have been many locking set screws, pin nuts, caps, etc. which have all solved the clinical challenges of the external nut, which by the way has been abandoned by the original designers.

The next comment for you is in regards to the anchor seat of the‘555 patent. The anchor seat of the ‘555 patent is used to lock the rod within the assembly. The bone screw of the ‘555 patent is allowed to freely pivot with a locked rod. This patent was applied to the “VLS” pedicle screw, a.k.a. the Variable Locking Screw. The pedicle screw was by design, able to lock the rod to the assembly and allow the bone screw to pivot to the anatomy of the patient and rod placement. The “hope” of the VLS was that the bone interface to the underside of the anchor seat would provide sufficient stability to the assembled construct in order to promote a bone fusion. Clinically this did not happen with much success. I have heard that not only did they continue to move in vivo but that many non-unions occurred. The VLS and thus the design rational of the ‘555 patent were abandoned. Claiming equivalence between the anchor seat of the ‘555 patent and the anchor seat of a multiaxial screw which locks that rod AND locks the bone screw is nonsense.

I hope my responses are helpfully. There are so many details of spine surgery that are too often overlooked or their importance not properly relayed in our patents. I know that switching from an external to an internal nut may not sound like much in many patents, but it made a tremendous difference to the surgeons and to the industry. From the corporate world, marketing a multiaxial screw with an external verse an internal wrench is worth millions of dollars. Lastly, the VLS screw "for fusion" can not hold a candle to a multiaxial screw with a locking bone screw.

Kind regards,

Nick

Post a Comment

<< Home

© 2004-2007 William F. Heinze