In Blanch v. Koons,

05-6433 (Oct. 26, 2006), the Second Circuit concluded that

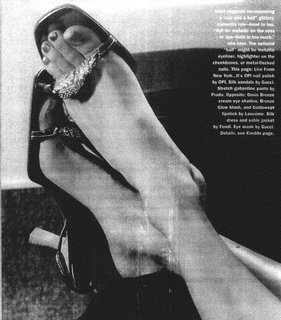

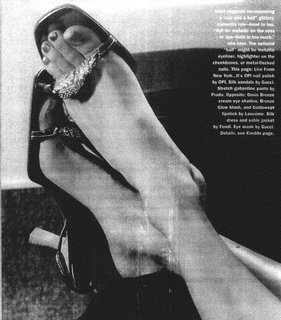

Jeff Koons' appropriation of "Silk Sandals by Gucci" by Andrea Blanch from the August 2000 issue of Allure magazine (above) for his "Niagra" collage (below) was fair use.

To create the “Easyfun-Ethereal” paintings, Koons culled images from advertisements or his own photographs, scanned them into a computer, and digitally superimposed the scanned images against backgrounds of pastoral landscapes. He then printed color images of the resulting collages for his assistants to use as templates for applying paint to billboard-sized, 100 x 140 canvasses. The “Easyfun-Ethereal” paintings, seven in all, were exhibited at the Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin from October 2000 to January 2001.

Like the other paintings in the series, “Niagara” consists of fragmentary images collaged against the backdrop of a landscape. The painting depicts four pairs of women's feet and lower legs dangling prominently over images of confections-a large chocolate fudge brownie topped with ice cream, a tray of donuts, and a tray of apple danish pastries-with a grassy field and Niagara Falls in the background. The images of the legs are placed side by side, each pair pointing vertically downward and extending from the top of the painting approximately two-thirds of the way to the bottom. Together, the four pairs of legs occupy the entire horizontal expanse of the painting.

In an affidavit submitted to the district court, Koons stated that he was inspired to create “Niagara” by a billboard he saw in Rome, which depicted several sets of women's lower legs. By juxtaposing women's legs against a backdrop of food and landscape, he intended to “comment on the ways in which some of our most basic appetites-for food, play, and sex-are mediated by popular images.” According to Koons, “certain physical features of the legs [in the photograph] represented for me a particular type of woman frequently presented in advertising.” He considered this typicality to further his purpose of commenting on the “commercial images ··· in our consumer culture.” Koons Aff. at ¶ 10.

Koons scanned the image of “Silk Sandals” into his computer and incorporated a version of the scanned image into “Niagara.” The legs from “Silk Sandals” are second from the left among the four pairs of legs that form the focal images of “Niagara.” Koons did not seek permission from Blanch or anyone else before using the image.

Deutsche Bank paid Koons $2 million for the seven “Easyfun-Ethereal” paintings. Koons reports that his net compensation attributable to “Niagara” was $126,877. Deutsche Bank received gross revenues of approximately $100,000 from the

exhibition of the “Easyfun-Ethereal” paintings at the Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin, a total that includes admission fees and catalogue and postcard sales. The record does not reflect Deutsche Bank's expenses for that exhibition other than the commission of the paintings.

The

subsequent exhibition of the paintings at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York sustained a net loss, although when profits from catalogue and postcard sales are taken into account, Guggenheim estimates that it earned a profit of approximately $2,000 from “Niagara.” fn.2 In 2004, the auction house Sotheby's reportedly appraised “Niagara” at $1 million. The work has not, however, been sold, nor does the record indicate that it or any other painting commissioned by Deutsche Bank has been offered for sale or been the subject of a bid.

Allure paid Blanch $750 for “Silk Sandals.” Although Blanch retains the copyright to the photograph, she has neither published nor licensed it subsequent to its appearance in Allure. Indeed, Blanch does not allege that she has ever licensed any of her photographs for use in works of graphic art or other visual art. At her deposition, Blanch testified that Koons's use of the photograph did not cause any harm to her career or upset any plans she had for “Silk Sandals” or any other photograph in which she has rights. She also testified that, in her view, the market value of “Silk Sandals” did not decrease as the result of Koons's alleged infringement.

Koons has been the subject of several previous lawsuits for copyright infringement. In the late 1980s, he created a series of sculptures for an exhibition entitled the “Banality Show” (“Banality”). In doing so, he commissioned large three-dimensional reproductions of images taken from such sources as commercial postcards and syndicated comic strips. Although many of the source images were copyrighted, Koons did not seek permission to use them. In separate cases based on three different sculptures from “

Banality,” two district courts concluded that Koons's use of the copyrighted images infringed on the rights of the copyright holders and did not constitute fair use under the copyright law. See Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 934 (1992); Campbell v. Koons, No. 91 Civ. 6055, 1993 WL 97381, 1993 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3957 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 1, 1993); United Feature Syndicate v. Koons, 817 F.Supp. 370 (S .D.N.Y.1993).

Unlike in those decisions, the Second Circuit concluded here that the use in question was transformative:

Koons asserts-and Blanch does not deny-that his purposes in using Blanch's image are sharply different from Blanch's goals in creating it. Compare Koons Aff. at ¶ 4 (“I want the viewer to think about his/her personal experience with these objects, products, and images and at the same time gain new insight into how these affect our lives.”) with Blanch Dep. at 112-113 (“I wanted to show some sort of erotic sense[;] ··· to get ··· more of a sexuality to the photographs.”). The sharply different objectives that Koons had in using, and Blanch had in creating, “Silk Sandals” confirms the transformative nature of the use. See Bill Graham Archives, 448 F.3d at 609 (finding transformative use when defendant's purpose in using copyrighted concert poster was “plainly different from the original purpose for which they were created”); see also 17 U.S.C. § 107(1) (first fair-use factor is the “ purpose and character of the use” (emphasis added)).

Koons is, by his own undisputed description, using Blanch's image as fodder for his commentary on the social and aesthetic consequences of mass media. His stated objective is thus not to repackage Blanch's “Silk Sandals,” but to employ it “ ‘in the creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings.” ’ Castle Rock Entm't, 150 F.3d at 142 (quoting Leval, supra, 103 Harv. L.Rev. at 1111). When, as here, the copyrighted work is used as “raw material,” Castle Rock Entm't, 150 F.3d at 142 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted), in the furtherance of distinct creative or communicative objectives, the use is transformative. Id.; see also Bill Graham Archives, 448 F.3d at 609 (use of concert posters “as historical artifacts” in a biography was transformative); Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures Corp., 137 F.3d 109, 113 (2d Cir.1998) (parody of a photograph in a movie poster was transformative when “the ad [was] not merely different; it differ[ed] in a way that may reasonably be perceived as commenting” on the original).

The test for whether “Niagara's” use of “Silk Sandals” is “transformative,” then, is whether it “merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” Campbell, 510 U.S.

at 579 (internal quotation marks and citation omitted, alteration incorporated); Davis, 246 F.3d at 174 (same). The test almost perfectly describes Koons's adaptation of “Silk Sandals”: the use of a fashion photograph created for publication in a glossy American “lifestyles” magazine-with changes of its

colors, the background against which it is portrayed, the medium, the size of the objects pictured, their details and, crucially, their entirely different purpose and meaning-as part of a massive painting commissioned for exhibition in a German art-gallery space. We therefore conclude that the use in question was transformative.

. . . Because Koons's appropriation of Blanch's photograph in “Niagara” was intended to be-and appears to be-“transformative,” because the creation and exhibition of the painting cannot fairly be described as commercial exploitation and the “commerciality” of the use is not dispositive in any event, and because there is insufficient indication of “bad faith,” we agree with the district court that the first fair-use factor strongly favors the defendants.

More about Jeff Koons

here.