Removeably Secured with One-Way Screws?

According to the majority opinion by Circuit Judge Clevinger, the Federla Circuit took issue with the district court's conclusion that the accused Graco juvenile car seat cannot infringe as a matter of law because it lacks a seat separate from a base and, at most, includes a base that is integral to the seat.

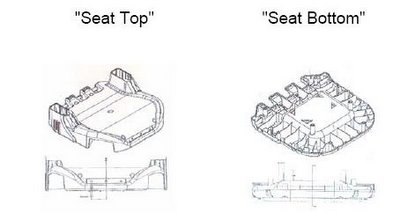

In the dissenting opinion, Circuit Judge Newman pointed out that the Graco carseat is a permanent assembly whose molded parts are permanently screwed together with six "one-way" screws. Upon unscrewing and disassembly, the Graco seat becomes a collection of loose parts, the cup holder incapable of its function of supporting a cup.The accused products comprise a top structure and a bottom structure, each easily removable from the other by an ordinary or one-way screwdriver, such that they are "removably attached" or "removably secured". However, whether the top and bottom structures of the Graco products are in fact the claimed "seat" and "base" of the asserted patents, such that the top structure is capable of functioning as a "seat" upon being removed from the bottom structure, is a question of fact that cannot be determined on summary judgment. We therefore vacate the summary judgment of noninfringement and remand the case to the district court to determine, as a matter of fact, whether the accused products meet the seat and base limitations of the asserted claims, and to decide any remaining issues.

The Dorel patents include drawings of the patented carseat, showing the separate base carrying the cup holders:

"The problem is not with the judges," writes The Good Professor, "but rather the arcane claim construction regime that has been built up long before Phillips: The simple 'purposive construction' elaborated by Lord Hoffmann for the House of Lords requires no special Markman hearing nor other bells and whistles to interpret claims -- nor any consideration of the file wrapper. While the United States struggles with patent reform, the failure to address claim construction as part of this exercise is incomprehensible."

The panel majority complains that the patent does not discuss the advantage of separating the Dorel seat from its base, stating that "there is no indication that the patent is directed to a product comprising a base that, during everyday usage, remains in the automobile while the user removes the seat and the child." Maj. op. at 5-6. However, such separable carseats were in the prior art at the time the Dorel applications were filed; the patents are directed primarily to the cup holders, not the seat and base structure. See '862 patent, col. 1, ll. 9-10 (describing the invention as a retractable cup holder in a "conventional juvenile vehicle seat" that is "generally known" and in "widespread use"); see also Figures 1 and 2 of Dorel's patents, supra. The record contains other patents by the inventor of the Dorel patents, such as U.S. Patent No. 6,554,358, which is directed to a seat removably attached to a base, and which cites eleven references to seat and base combinations that are manually separable. In addition, Graco points to Department of Transportation regulations, with which all carseats must conform, that describe carseat components that "can only be removed by use of a tool" as "permanently attached." 49 C.F.R. §§571.213 S5.9, 571.225 S15.1.2.1(f). The panel majority's interpretation of "removably attached" and "removably secured" as requiring only that the structure be "capable" of disassembly, however laborious the mechanics, is contrary to the prior art, contrary to usage in the field, and contrary to federal regulation.

The majority's approach to claim construction strains this court's attempts to restore consistency of analysis to patent claims by placing the claims in the context of the specification. See Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1321 ("The risk of systematic overbreadth is greatly reduced if the court instead focuses at the outset on how the patentee used the claim term in the claims, specification, and prosecution history, rather than starting with a broad definition and whittling it down"). The panel majority construes the Dorel claims as encompassing a different invention from that described and prosecuted. From this incorrect claim construction, leading the court to an incorrect decision, I must, respectfully, dissent.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home

© 2004-2007 William F. Heinze